What is a serological test?

Countries are scrambling to test hundreds of thousands of people to see if they are infected by the coronavirus. That test, which employs a technique called PCR, looks directly for the genetic material of the virus in a nasal or throat swab. It can tell people with worrisome symptoms what they need to know: Are they infected right now?

But a swab cannot tell you if you’ve had the disease in the past—which means we may not understand the full extent of its spread, or whether large numbers of people have already been infected and recovered without showing symptoms.

The answer to this is a different kind of test, one that can look at people’s blood to find the telltale traces that show if somebody’s immune system has been in contact with the virus. This procedure, known as a serological test, asks a different question—not “Does this person have coronavirus?” but “Has this person’s body ever seen the germ at all?”

The answer to this is a different kind of test, one that can look at people’s blood to find the telltale traces that show if somebody’s immune system has been in contact with the virus. This procedure, known as a serological test, asks a different question—not “Does this person have coronavirus?” but “Has this person’s body ever seen the germ at all?”

Serological tests work on blood samples rather than nasal swabs. These types of test for coronavirus are being developed by a number of labs around the world. The blood of someone who has been exposed should be full of antibodies against the virus. It’s the presence, or absence, of such antibodies that the new tests measure. Among those developing such tests are researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine in New York City, led by Florian Krammer.

How does it work?

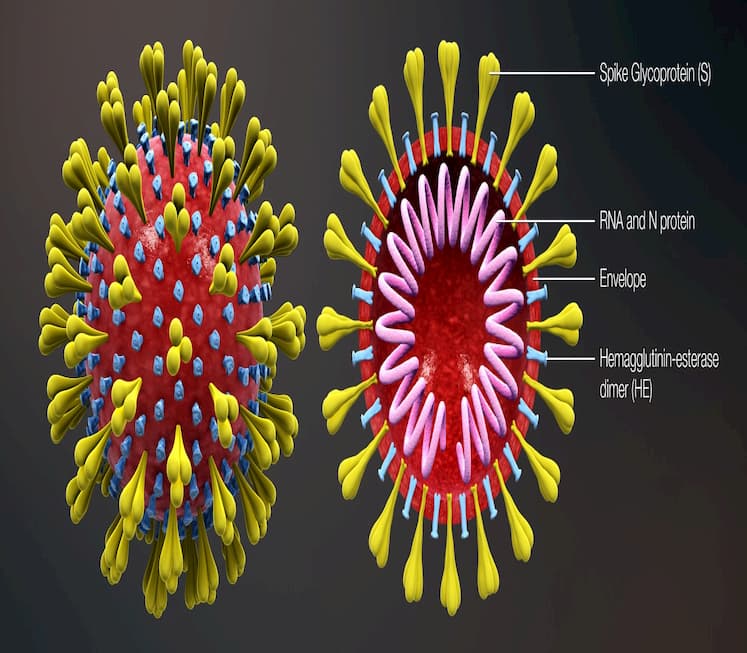

To make their version of a test, the Icahn team produced copies of the telltale “spike” protein on the virus’s surface. That protein is highly immunogenic, meaning that people’s immune systems see it and start making antibodies that can lock onto it. The test involves exposing a sample of blood to bits of the spike protein. If the test lights up, it means that you have the antibodies.

To check their results, the team inspected blood samples collected before covid-19 came out of China this year, as well as blood from three actual coronavirus cases. According to Krammer, the test can pick up the body’s response to infection “as early as three days post symptom onset.”

What impact could testing have on treatment?

Krammer believes serological testing could have immediate implications for treatment by helping locate survivors, who could then donate their antibody-rich blood to people in ICUs to help boost their immunity.

What’s more, doctors, nurses, and other health-care workers could learn if they’ve already been exposed. Those who have—assuming they are now immune—could safely rush to the front lines and perform the riskiest tasks, like intubating a person with the virus, without worrying about getting infected or bringing the disease home to their families. But tests could have a bigger impact too.

What else can it tell us?

How widespread is the new coronavirus? How many people get it and don’t even know? What is the actual death rate? Those are some of the biggest questions that science doesn’t have the answers to yet.

Serological tests, if they are done widely and quickly enough, could give an accurate picture of how many people have ever been infected. And that is the figure disease modelers and governments urgently need to gauge how deep society’s shutdown needs to be.

The real fatality rate among everyone infected is possibly much lower than current figures tell us.

At the time of writing, the coronavirus had killed more than 52,000 people, or about 5% of the confirmed cases: a shocking death rate. But the real fatality rate among everyone infected by the virus is certainly lower, and possibly much lower, than current figures can tell us. The reason epidemiologists can’t say for sure is that they don’t know how many people are infected but never go to the hospital or even have symptoms. And that’s a huge problem for setting policy.

John Ioannidis of Stanford University argued in the publication Stat that the true death rate could be less than that of the seasonal flu. If so, “draconian countermeasures” are being implemented amid an “evidence fiasco” of “utterly unreliable” data about how many people are infected. Another report, meanwhile, estimated that early in the outbreak only 10% to 20% of the actual infections were being documented. Without more testing, nobody can be truly certain what the next steps should be.

What next?

Other scientific centers, in Singapore and elsewhere, also say they have antibody tests running, as do some US companies selling products to researchers. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says it is developing one; the UK planned to produce millions of at-home testing kits that use finger pricks of blood, but they have run into difficulties with accuracy.

To learn the true extent of infections, the next step for researchers—in New York or elsewhere—is to carry out “serological surveys” in which they’ll do the test on blood drawn from large numbers of people in an outbreak area. That may tell them exactly how many cases have gone unnoticed.

But it could be some time before scientists learn the answer. Krammer says the effort to carry out a wider survey is “just starting.”

Originally published on MIT Technology Review by Antonio Regelado

You might also like

For relevant updates on Emergency Services news and events, subscribe to EmergencyServices.ie